‘Once fire season rolls around, there’s really no typical day.’

Francesca Fionda 27 Oct 2022TheTyee.ca

Francesca Fionda is a Tyee contributing reporter and freelance investigative and data journalist based on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) nations.

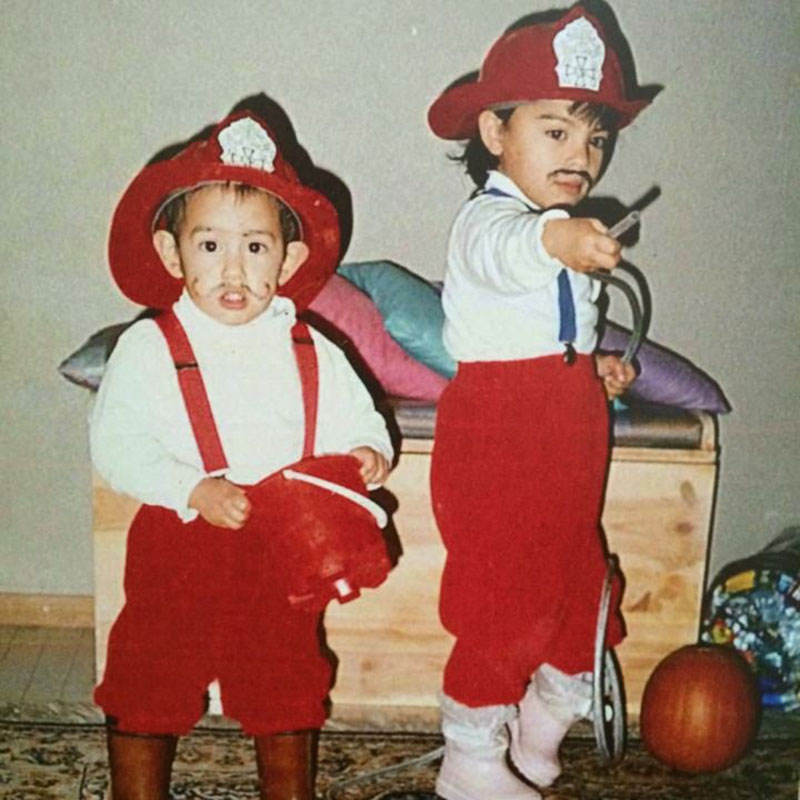

It all started with him copying my Halloween costume.

Four lucky readers will get free passes to the Vancouver Opera’s winter performance.

Well, that’s how I tell the story of how my brother became a smokejumper. In reality, Enrico Fionda spent years studying forestry at UBC and many more years gaining experience on the ground fighting wildfires.

He’s been a firefighter for 13 years, nine of which have been as a smokejumper with the BC Wildfire Parattack program. That means, at times, he jumps from a plane to get to hard-to-reach-fires as quickly and efficiently as possible. Enrico estimates he’s done well over 100 jumps in his career so far. Our mom got used to the idea around the 99th jump.

The BC Wildfire Parattack program employs the only smokejumpers in Canada. They’re based out of Fort St. John, where my brother lives, and Mackenzie, about 180 kilometres north of Prince George. I got to visit the base in Fort St. John last winter, when things were a lot calmer than they are over the summer. The job requires a lot of diverse skills and is a lot more than physical labour, Enrico told me.

There were long wooden tables where the crew could spread out their chutes to inspect for any rips or tears and pack them back up. There was a small gym space to work out, offices to plan strategy and scheduling, a lunchroom and a locker area filled with gear and various dry goods.

But the thing that stood out to me most was the loft space upstairs dedicated to sewing machines. “We make all of our own gear,” my brother told me when I interviewed him at the end of the summer about what a day in the life of a smokejumper is like. During my visit he showed me the padded Kevlar suits that protect smokejumpers from tree branches and hard landings, and can even float in case someone lands in the water.

“All this gear is very specialized,” he told me. That means when they aren’t on a fire, a lot of time is spent building or repairing their gear.

Here’s the rest of our conversation. It’s been edited for length and clarity.

How do you describe your job to people?

I’m a wildland firefighter, and more specifically a smokejumper. My job is to put out wildfires or forest fires which are basically vegetative fires; so non-structural, non-vehicular fires that involve vegetation, trees or grass. Being a smokejumper just means that we access the fire in different ways. Rather than driving to a fire or taking a helicopter, our primary mode of transportation is through a fixed-wing aircraft or airplane. Typically, we parachute to the fire. Sometimes we’ll drive as well. Sometimes we will take a helicopter.

You said “non-structural.” What happens when a fire gets close to a community or structures?

If there are structures involved, we will likely be on site as well. But our focus is the forest or the vegetation. We’ll work with structural fire departments who put out the actual buildings, but in a large forest fire we will sometimes set up structure protection. So we will protect the buildings from a forest fire, but we don’t actually put out the buildings themselves.

Why do you have to jump into these spots?

The idea of smoke jumping is to deliver firefighting resources faster, often to more remote locations. An airplane can travel significantly faster than a helicopter or a truck and it can access locations that may be more difficult using other methods. Because the airplane can fly for longer durations without needing fuel, it can access some of the more remote locations. It can also carry a lot more gear than a helicopter. We have two aircrafts. The larger one can carry 13 jumpers along with quite a bit of gear. We have a second aircraft that carries seven jumpers and all their appropriate gear. We can travel faster, carry more gear, travel further and it’s more cost effective.

How do you decide when you’re going to jump?

If we get a dispatch to a fire, we load up the airplane and fly overhead. We have to do an assessment and then we work with the operations in Prince George Fire Centre to determine whether it’s appropriate to deploy.

How close do you get to a fire? Can you paint a picture of what that’s like?

Depending on the terrain and if there’s a suitable location to jump, you could be right next to the fire or you could be a couple of kilometres away — it’s all very circumstantial. Wind, topography, the fire’s behaviour, access and jump spot availability are all factors that play a role. So you might be right next to it, or you could be a couple kilometres away and have to hike in.

How complicated is it to determine that?

On board, we have a spotter who’s in charge of the jump operations and they’ll work with the jumper in charge, basically the first person to exit the aircraft. And they’ll usually assume the command of the fire. The spotter remains on the aircraft and they work together to come up with a plan before they jump. Overhead in the airplane they’ll circle around, they’ll complete an initial fire report, which has basic information about the fire size and any values threatened. Then once that information is relayed to operations in the fire centre and the go ahead is given to action the fire, the spotter and the jumper in charge will pick a spot that they’re comfortable jumping and then go from there to deploy the crew.

What does a typical day look like for you?

It’s quite variable. In the spring, we’re often doing a lot of training. And then once fire season rolls around, there’s really no typical day. If it’s not too busy, the crew will have about an hour to do fitness. Then we have a big morning meeting and talk about who’s on standby for the day or for the week and check the weather forecast. Then check over your gear, make sure the plane is loaded correctly. And then depending on what the needs are, people will either be packing parachutes, or packing gear, or doing training. Once we receive a fire, everybody heads to suit up and load the aircraft.

Does the whole team go?

I think there are about 65 active jumpers in British Columbia. Depending on the hazard, a number of them will be on standby. A typical load on one of the aircrafts is 13 jumpers, and they would be the first to load up if there was a fire call.

Once you’re on the ground, what do you start doing?

Once you’re on the ground and you’ve gathered your parachute, then the airplane will drop the cargo needed to put out the fire. It will deploy chainsaws, pumps and hoses and overnight gear for the crews. They are able to be self-sufficient for 48 hours. And they’ll throw fuel and a first aid kit for the crew as well.

What do you start doing after the gear lands?

Normally you’ll have some of the crew cutting around the fire’s edge, removing the fuel. Basically they’ll cut a trail around the fire, and you’ll have others setting up the pump and running the hose out to the fire’s edge to start spraying it out.

How do you get water to remote sites?

Normally we’ll have to find a natural water source as close to the fire as possible.

Would it happen that there’s a fire too far from a water source?

Sometimes, depending on the fuel type, you can put out some fires without any water by digging around it. But usually there’s some sort of water source within a few kilometres that you can use. If there’s a road, you can have a water truck deliver water. And then in some instances, you can use a helicopter to fill up water bladders; basically big, portable swimming pools. You can put several pumps on a hose system to carry water for kilometres.

What’s the most remote site you’ve ever been on?

There are lots of areas that are very, very remote in B.C. There was one fire on the top of a mountain and we had to jump at the bottom and hike up. If there’s no suitable opening for a helicopter or for jumpers then you might have to find an opening that could be a few kilometres away.

How long do you spend in remote communities while you’re doing this? Where have you worked?

One of the cool things about the smokejumper program is that you can end up basically anywhere in B.C. within a few hours. It takes about three hours and we can fly from Fort St. John all the way to Vancouver Island. There’s days where we fly across the province. There are some very remote communities up north of Mackenzie. We’ve also been in Atlin and areas around there.

You’re specifically trained to reach remote areas. Do you get called to help out outside of B.C.?

We have actioned fires in Yukon before. And then we have worked with smokejumpers in the States as well. We’ve sent jumpers up to Alaska and down to Montana before. We’ve also had their smokejumpers come up to B.C.

Being so close to the fires are you worried about smoke inhalation? And do you do anything to mitigate the possible health impacts?

Yes, smoke is definitely a concern. Normally when you’re actioning a fire, you’re upwind of it, because that’s the safest place to be. You wouldn’t want to be downwind of a fire because usually the wind is going to push the fire in that direction. If you’re upwind of the fire, you’re generally in a better spot. You’re usually out of the smoke, but it definitely is smoky at times.

What’s the longest fire you’ve ever been on?

We can be on a fire for up to 14 consecutive days.

What happens after that to the crews?

They need to take time off.

So how often does that happen?

Pretty regularly. Generally what we do is the initial attack. So usually we’re deployed to smaller fires, and we can usually have a handle on them over a few days. But then we could be back out on a new fire the next day. It’s pretty common for us to be working 14 days on various fires.

They’ll jump a fire, put it out, come back, maybe they’ll have a day in town to get their gear re-upped and then could possibly be on a fire the next night. It depends how busy we are. But it’s not uncommon to be out on the line for seven plus days.

What do you mean by initial attack?

Initial attack is when we’re the first to respond to a new fire as it’s reported, and then once the fire has passed initial attack, it’s called sustained action.

What’s your favourite campfire recipe?

We eat off a campfire quite a bit and you can’t beat a good steak. I would say that’s my go to. We have a bit of a tradition where people experiment with different Spam recipes. Gatorade on Spam is surprisingly a good combination.

What?!

Spam with Gatorade powder sprinkled on top, cooked over a campfire, caramelizes it. Once I had McDonald’s burgers frozen reheated on the fire. It was pretty good.

How do you get you and your gear out after you’re finished working on a fire?

It depends on the location of the fire and how much we can hike out to a road. Oftentimes we’ll use a helicopter to help move the gear and the people to the closest airstrip where an airplane can come and pick us up.

What’s the most challenging part of your job?

I think maybe the most challenging part is the unknown of every day. No fire’s the same and every mission is going to be different. So just being prepared for the unexpected and being able to adapt quickly.

What’s the closest call you’ve had?

There’s lots of risks in wildfire. But I’d say our safety record is pretty good. We do a lot of training and focus on safety. My first year firefighting, on the way to a fire, I was in a helicopter where the main rotor hit some trees. Luckily, we didn’t crash, but there was quite a bit of damage to the helicopter.

What mental skills are important for this work?

Being able to focus on very different tasks. I could be in the office one day doing paperwork, and then get a fire call and all of a sudden be jumping onto a fire and then falling trees all within a few hours. Keeping your focus and your situational awareness, so that you’re safe, is challenging. It can take quite a bit of skill.

What do you think would surprise people most about this work?

I think there’s a big misconception that firefighting is just a labour job, and that it’s very mindless, or it doesn’t take skill or training and I think that couldn’t be any more inaccurate. There’s a lot of training that goes into the job. There are skills that you gain through doing the job for years that you can’t teach.

Even understanding how fires burn. Oftentimes, you’re making decisions without having all the facts in front of you so you need to draw on experiences in order to make safe and effective decisions when you’re putting out a fire.

Even just finding smoke through smell. When a fire is almost out, we have to patrol it. So we’ll walk around the fire, trying to find little spots that are still burning. Being able to sniff the smoke and find it is a skill that you can’t just teach. You need to be able to do it after years of practice and that’s just one very small part of the job that gets lost without experience.

What motivates you to do this work? Why do you like this job?

I think for me, it’s the people I work with. Everyone who’s there is very motivated and we are able to push each other to be better. I find they’re inspiring because everybody wants to do their best and it raises everybody up. They’re very talented and hardworking people.

What does the offseason feel like? How do you gear down after so much high-adrenaline work?

A Continent Transformed by Wildfire, Then and Now

Spending time with family and friends that I didn’t get to during the fire season and getting back into a routine. A lot of the smokejumpers are seasonal, which can be hard for some people because they leave a busy season and then they might not have work lined up for the winter. Some of them are back in school so it’s quite a change of pace. Keeping in touch with co-workers is important and we have a pretty good community. So I think that helps. I think after a busy season, a lot of people do want to just travel and take some time off. I think it’s healthy in a lot of ways. Training and getting ready for next season keeps a lot of people motivated.

Last question, does it feel like things are getting worse from year to year?

I think things are getting worse. 2017, 2018 and 2021 were some of the worst seasons we’ve seen in B.C. I think part of it is that communities have expanded into new areas as well. There’s more values on the landscape now that are threatened, whether it’s the fire that’s more intense, or just the fact that there’s more things out there that we don’t want to burn.

Do you think that climate change has anything to do with that?

I think so. The fires seem to be more intense and the season starts earlier and goes longer. You can look up the trends and you’ll see it right there average hectares burned, or length of fire season. You can’t argue with science; the science exists. ![]()